Saturday, October 27, 9.30 pm

Saturday, October 27, 9.30 pm

Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Matriz)

Gonçalo de Baena, musician of D. João III, and the Europe of his time

Bruno Forst, organ

It was in the 16th century that organ music was born. Initially limited to modest improvisations on a liturgical cantus firmus and to the performance of vocal pieces sustaining (or replacing) the voices, it gradually moved away from those models in order to become a genuinely instrumental repertoire. In the Iberian Peninsula, the glosa had an important role in this process, creating, little by little, on the basis of pre-existing works, an innovative and brilliant style.

We know the repertoire of Iberian organists of the beginning of the 16th century thanks to the Arte novamente inventada pera aprender a tanger (Lisbon 1540) by Gonçalo de Baena, a Castilian musician in the service of King John III. In this book we find, on the one hand, contrapuntal pieces for two or three parts based on Gregorian hymns (Pange Lingua, Ave maris stella and Conditor Alme), written vestiges of a tradition of improvisation and, on the other, literal transcriptions of vocal works which, according to Baena’s indications, may be played as they are written or ornamented with small glosas which give the music a more instrumental character. This anthology also contains all the known works of the Portuguese composer António de Baena, whose superb Agnus Dei, based on the obsessive repetition of a four-note motive (F-D-E-D) gives some idea of his genius.

The Libro de cifra nueva, published in 1557 by Venegas de Henestrosa informs us concerning the development of technique: the glosas are no longer left to the performer’s imagination, but are written out and, to the name of the author of the glossed work is associated that of the glosser, making him a kind of co-author. In addition, in pieces such as Conditor Alme by Gracia Baptista (the first woman mentioned in the history of Iberian music) one feels the influence of the glosa. Finally, there are some instrumental works where the repetition is completely glossed, such as the Pavana by Cabezón.

It is with the latter that the glosa reached its apogee. In the Obras de Música, compiled in 1578 by his son Hernando, the glosas have an important position. The vocal works, very often complex, which serve as their basis, are no more than a pretext for the creation of profoundly instrumental original works. The name of the glossed author is, indeed, only mentioned as a source of inspiration for a piece whose paternity is entirely attributed to the glosser.

From then on, it was but a step for the glosa to free itself from vocal models and become an independent genre. This step was taken at the end of the century and concerning this we have the testimony of Francisco Correa de Arauxo. In his Facultad Orgánica of 1626, this Sevillian organist organizes all his tientos on the basis of brief melodic themes which generate their own glosa within a fluid and inspired discourse. On the edge of the great passion for Italian music which would overtake Europe, the last lights of the Iberian repertoire born in the 16th century shine in all their splendour...

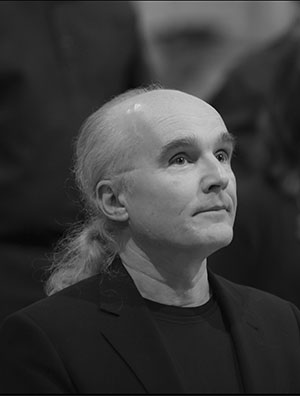

Bruno Forst

GONÇALO DE BAENA

Arte novamente inventada pera

aprender a tanger (Lisboa 1540)

João de Badajoz (c. 1460-p.1521)

¬ Pange lingua

Firmin Caron (?-1475)

¬ Hélas que pourra devenir mon cœur

Josquin Desprez (c. 1440-1518)

In pace in idipsum

Loyset Compère (c. 1450-1518)

¬ 1º tono

Francisco de Peñalosa (c. 1470-1528)

¬ Unica es colomba mea

Annonym

¬ Conditor alme syderum

Gonçalo de Baena (c. 1480-p.1540)

¬ Ave maris stella

Antonio de Baena (?-p.1562)

¬ Agnus dei (Missa fa-re-mi-re)

Venegas de Henestrosa

Libro de cifra nueva (Alcalá de Henares 1557)

Francisco Fernández Palero

(c. 1533-1597)

¬ Quaeremus cum pastoribus

Gracia Baptista (fl.1557?)

¬ Conditor alme siderum

Antonio de Cabezón

Obras de música (Madrid 1578)

Antonio de Cabezón (1510-1566)

¬ Pavana

¬ Ardenti mei sospiri

Francisco Correa de Arauxo

Facultad orgánica (Alcalá de Henares 1626)

Francisco Correa de Arauxo

(1584-1654)

¬ Cuarto tiento de 4º tono

¬ Medio registro de tiple de 10º tono

¬ Segundo tiento de primer tono

Participants

|

Bruno Forst was born in Troyes. He began his piano and organ studies with Paule Rochais in Cognac. Later, after studying philosophy, he studied in the class of Francis Chapelêt at the National Conservatoire of the Bordeaux Region, from which he graduated with a gold medal in 1996. He then left for Madrid, where he studied under Miguel del Barco. He settled in Spain, which had become his preferred country, given his passion for the baroque organs in which the country is so rich. He lives currently in a small village in the province of Soria, where he devotes himself to the study of Spanish musical sources of the 16th and 17th centuries. There he prepares his recordings and concerts of organ, harpsichord, clavichord and chamber music, which he gives in Europe, the United States and Latin America. He has made a transcription into modern notation of the keyboard tablature by Gonçalo de Baena, Arte novamente inventada pera aprender a tãger, printed in Lisbon in 1540 (Dairea Ediciones, 2012) and has recorded for the Brilliant Classics label several CDs of Iberian organ music. |

Notes about the organ

Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição, Machico

In the historical documentation from before the 20th century there are references to two instruments: according to historical tradition, one was given to the Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição in 1499 by King Manuel, and another acquired in 1746. As regards the Manueline organ, we may deduce that it was placed within the archway above the choirstalls on the Gospel side of the sanctuary. In the 18th century, the state of this instrument must have left much to be desired, leading to the acquisition of the second instrument in 1746. The organ arrived in Madeira in 1752, with the Council of the Treasury initially contributing the cost of purchase and later the installation costs.

The recent restoration undertaken by Dinarte Machado was done with the principal objective of returning as far as possible it to its original constitution, in accordance with indications to be gleened from the pieces of the instrument during its dismantling. Thus, the restoration always proceeded from a philosophy of taking into account the specificities of the original pieces, from the configuration of the case and its polychrome decoration, to the way the registration, pipework, bellows-work and even its placement - in the sanctuary - were returned to how they were originally. As regards the composition of the stops, the split keyboard, with the reed stop in the right hand, which the organ indicated was an original feature, which indeed characterised the instrument. The original keyboard, which was found piled in a heap, and which it was possible to repair and reassemble retains the short octave, as was usual at this period. The new pipework was completed with great rigour in accordance with the characteristics of the few original pipes that had survived, compared with the actual indications and dimensions of the windchest, which was also studied and recorded in great detail.

There can be no doubt that this is one of the loveliest organs on the island of Madeira. It is one of the instruments that conserves some of the most typical features of Portuguese organ building in the 17th century. It should be stressed that the restoration work carried out on this instrument required study of considerable documentation, as well as comparison with other instruments of the period. Since no other instruments of this kind are to be found in Portugal, recourse was had to instruments from other countries for the necessary data.

Manual (C, D, E, F, G, A-c’’’)

Flautado de 12 palmos (8’)

Flautado de 6 palmos (4’)

Flauta doce

Dozena (2 2/3’)

Voz humana (c#’-c’’’)

Quinzena (2’)

Composta de 19ª e 22ª

Sesquialtera II (c#’-c’’’)

Clarim* (c#’-c’’’)

* horizontal reeds

Bruno Forst

Bruno Forst